Introduction

The idea of Open Government Data (OGD) has seen rapid diffusion across the globe. At the end of the last decade few governments had engaged at all with the idea of open data, and the number of OGD initiatives could be counted on one hand. By mid-2013 the concept of OGD has spread across the globe. There are now OGD portals and projects to be found on every continent, and in an increasing number of cities and international institutions. Open data has made it into strategies and actions plans at the highest levels, from Open Government Partnership National Action Plans, to the G8 Open Data Charter, and from initiatives on open data in Aid, Extractives and Agriculture to the UN High Level Report on the Post-2015 Development Agenda, which calls for a ‘data revolution’ incorporating a move towards open data.

However, amongst this dramatic progress, diffusion of the open data idea has not been equally experienced across geographies and sectors; nor have the potential benefits of open data been locked-in. There is still a long way to go before the democratic, social and economic potentials of open data can be fully realised in every country, and – even where contextual factors are conducive to open data supply and use – many OGD initiatives are presently resting on shallow foundations, at risk of stalling or falling backwards if political will or community pressure subsides.

In the Open Data Barometer we have sought to capture a snapshot picture of OGD around the world. The macro-level picture presented in this report is informed by, and complements, our on-going qualitative research work to explore open data readiness, open data use, and emerging impacts of open data, in different country contexts and sectors across the world. We start from the assumption that there is no one-size-fits-all approach of securing the benefits of open data. The Barometer is designed to help us understand both common progress, and different pathways, towards unlocking benefits from OGD. By creating a composite index from the indicators gathered for the Barometer we hope to raise questions about how OGD in different countries compares, and by breaking this down into a range of sub-components we aim to illustrate the many different elements that may be important to effective OGD policy and practice.

Above all, the Open Data Barometer is a piece of open research. All the data gathered to create the Barometer will be published under an open license, and we have sought to set out our methodology clearly, allowing others to build upon, remix and reinterpret the data we offer. Data collected for the Barometer is the start, rather than the end, of a research process and exploration.

The promise and realisation of open data

Open data has many roots and many branches. Different groups have come together to advocate for Open Government Data based on the potential for it to lead to:

More efficient and effective government – both through government using its own data better, and through innovators outside of government identifying improved ways to provide public services, meeting the diverse needs of citizens through digital technologies;

Innovation and economic growth – acting as a 21^st^ Century infrastructure, and a raw material, for activity in the information economy. Start-ups and established businesses can use open data to generate new products and services, and secure efficiencies, generating a net-gain for country economies;

Transparency and accountability – allowing citizens and civil society to see, understand and monitor better what their governments and the private sector are doing, challenging corruption or unaccountable activity, and finding opportunities to influence policy and practice;

Inclusion and empowerment – enabling marginalised groups to get involved in the political process, and removing imbalances of power created through information asymmetry.

Taken together these potential outcomes provide a strong argument in favour of shifting to ‘open by default’ for all the non-personal data governments collect. Right now, much of the value of government held data remains locked-up.

However, just because OGD in the abstract is a common ingredient to all these forms of change, that does not necessarily mean that any and all open data help secure any and all outcomes. There will be different datasets and different pre-requisites involved in securing different kinds of open data impact. Meanwhile, across different countries the range of quality of data that is ‘locked up’ inside government, and the relative costs of getting it out, will vary. In the Open Data Barometer we’ve measured a range of factors that affect the capacity of government, citizens and civil society, and entrepreneurs and business to secure the benefits from open data, and we’ve looked at a breadth of datasets, from those primarily useful for accountability, to those that provide key foundations for building innovative businesses.

In the pages that follow we take a broad look at how far the promise of open data is being delivered, and outline some of the current challenges to be met in further securing the potential.

Key facts: methodology

The Open Data Barometer is based upon three kinds of data:

A peer reviewed expert survey carried out between July to October 2013, asking researchers to provide a score from 0 – 10 in response to a range of questions about open data contexts, policy, implementation and impacts. Scores were normalised (using z-scores) prior to inclusion in the Barometer.

Detailed dataset assessments also completed by our expert researchers, reviewed through a double-blind review process, and subsequently verified by a technical expert. These assessments were based on a 10-point checklist, completed for 15 kinds of data in each country, touching on issues of data availability, format, license, timeliness and discoverability. Each checklist answer is supported by qualitative information and detailed hyperlinks, and checklist responses are aggregated to provide a 0 – 10 score for each dataset. These are presented in their original form, to allow comparison between datasets, and are averaged to give a dataset implementation sub-index. This sub-index is normalised (using z-scores) prior to inclusion in the overall Barometer calculations.

Secondary dataselected to complement our expert survey data. This is used in the readiness section of the Barometer, and is taken from the World Economic Forum, United Nations e-Government Survey, and Freedom House. The data is normalised using z-scores prior to inclusion in the Barometer.

The list of countries included in the 2013 Barometer is based upon the Web Index (thewebindex.org) sample, which was designed to represent a broad range of different regions, political systems and levels of development. It also supports further interrogation of ODB data alongside data from the forthcoming 2013 Web Index.

Open data diffusion: rapid but unequal

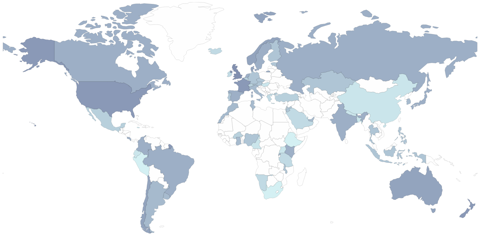

In the Open Data Barometer sample of 77 diverse states across the world, over 55% have developed some form of Open Government Data (OGD) initiative, with over 25% of the total sample establishing initiatives with dedicated resources and senior level political backing. The map below demonstrates both the global extent and depth of government level activity on open data, yet also reflects the unequal diffusion of OGD practices.

Figure 1: Heatmap of scores for expert survey question: 'To what extent is there a well-resourced open government data initiative in this country?' Higher scores (darker colours on the map) indicate a well-resourced initiative, with strong political commitment. Countries in white were not included in the Open Data Barometer study.

The Open Data Barometer survey asked a range of questions to explore the extent of OGD adoption in different countries, including: establishing whether underpinnings for OGD were in place through Right to Information (RTI) laws; whether central government had an OGD initiative; whether city or regional governments were running OGD initiatives; whether there was demand from civil society and the technology community for OGD; and whether governments were providing support for OGD re-use through training, innovation events, grants and voucher schemes. By looking at these different dimensions we are able to get a sense of how broad-based existing OGD initiatives are.

| Regions | Right to Information Laws | OGD Initiative | Demand from civil society & technologists | Government support for OGD innovation | City or regional OGD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 35.71 | 28.57 | 28.10 | 14.81 | 5.29 |

| Americas | 60.77 | 50.77 | 42.31 | 29.06 | 34.19 |

| Asia Pacific | 56.92 | 50.00 | 46.15 | 29.06 | 23.93 |

| Europe | 61.36 | 55.45 | 61.82 | 38.89 | 47.47 |

| Middle East & C. Asia | 22.50 | 38.75 | 21.25 | 8.33 | 8.33 |

| Total | 49.48 | 44.68 | 42.47 | 25.83 | 25.69 |

Table 1: Regional breakdown of Open Data Barometer survey responses. Mean average of normalised (z-score) and scaled values. OGD Initiative variable in bold. Higher scores are better.

As Table 1 above highlights, the Americas, Asia Pacific and Europe have broadly comparable scores when it comes to the presence of OGD initiatives, but greater variation can be seen when it comes to civil society and technologist demand for OGD and government support for innovation. Across all the areas surveyed, government support for innovation is low, suggesting an emphasis on getting data online, but less attention being paid to supporting re-use of data. Table 1 also highlights that at present it is more common for countries to have OGD initiatives at the national level, rather than the city level, although there are some notable exceptions emerging, such as Nigeria, where Edo State has recently launched an OGD portal ahead of the presence of a national government portal.

Looking at the same data, grouped by the 2012 Human Development Index ranking of the countries concerned (Malik, 2013), we see a strong relationship between levels of development and variables concerning the diffusion of OGD policy and practice (Table 2).

| Regions | Right to Information laws | OGD Initiative | Demand from civil society & technologists | Government support for OGD innovation | City or Regional OGD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very High | 57.81 | 59.69 | 60.31 | 40.28 | 45.14 |

| High | 48.75 | 43.13 | 31.88 | 18.06 | 22.22 |

| Medium | 40.00 | 40.91 | 34.55 | 18.18 | 12.12 |

| Low | 41.11 | 21.67 | 25.00 | 11.73 | 2.47 |

| Total | 49.48 | 44.68 | 42.47 | 25.83 | 25.69 |

Table 2: Average score by HDI Rank, normalised and scaled variables from expert-survey.

It is notable however, that the gap between medium and high HDI countries is narrow with respect to the presence and strength of OGD initiatives, and that demand from civil society and technologists appears marginally stronger in medium HDI than in those with a high HDI rank.

Open data readiness

Successful OGD initiatives need more than just datasets. They also need intermediaries, able to take government data and turn it into platforms and products with social and economic value, and re-users equipped to access and work with data in different ways. This is sometimes talked of as the need for an ecosystem around the core data infrastructures of an OGD programme. In recognition of this, the Open Data Barometer looks at a number of different variables as part of assessing a country’s capacity to secure and sustain the full benefits of open data.

For analysis we divide the Open Data Barometer readiness variables into three components. These are:

- Government capacity and the presence of government commitments to open data, addressing the political will and organisational ability of governments to both make open data available, and to secure benefits from open data, such as increased operational efficiency.

- Citizen and civil society freedoms and engagement with the open data agenda, including the presence of strong Right to Information and Data Protection regimes, which exploratory research in the Open Data in Developing Countries project (Davies, Perini, & Alonso, 2013) has suggested are important for empowering citizens to hold government to account, and protecting citizens from potential abuses of open data.

- Resources available to entrepreneurs and businesses to support economic re-use of open data and to catalyse intermediary actions, including internet penetration, the availability of training for businesses, and government support for open data led innovation.

The readiness variables selected were also designed to cover all six dimensions of open data readiness (Alonso, 2011): legal, political, social, economic, organisational and technical capacity, recognising that effective open data initiatives require engagement of a broad range of actors in society (Hogge, 2010).

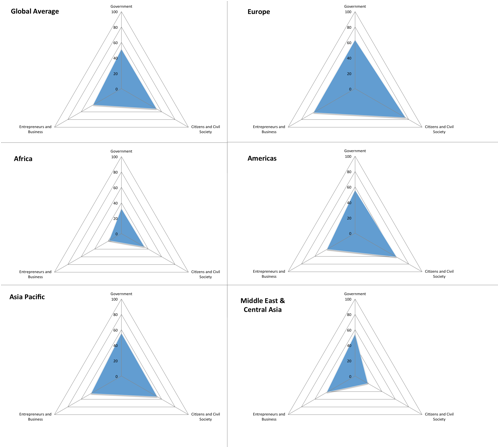

The radar charts in Figure 2 below present a regional breakdown of the ODB readiness component.

Figure 2: Radar charts showing scaled component scores in the readiness sub-index by region.

The low open data readiness in Africa is particularly impacted by limited internet penetration, and a scarcity of training for the entrepreneurs and civic technologists who often act as key intermediaries between open data, and wider use of that data. Developing open data on the African continent may require both substantial focus on building the capacity and sustainability of such intermediaries, as well as exploring different approaches to making data accessible that do not rely on Internet penetration, such as through print media, community radio and mobile phones.

By contrast, in the Middle East and Central Asia, there is reasonably strong technical capacity, but limits on civil society freedoms, and the absence of strong Right to Information laws to back up civil society use of open data lead to much lower citizen and civil society readiness to secure benefits from open data. The presence of open government data portals in a number of countries with low civil society readiness (Kazakhstan, Bahrain) raises questions about open data policy transfer taking place at the elite level, with open data potentially developed largely as an ‘e-government’ project, rather than as part of broader based open government initiatives involving governments, private sector and civil society.

In following chapter we look at a number of country case studies to explore in more depth the different paths that countries are taking to open data readiness and implementation.

Implementation: dataset availability and accessibility

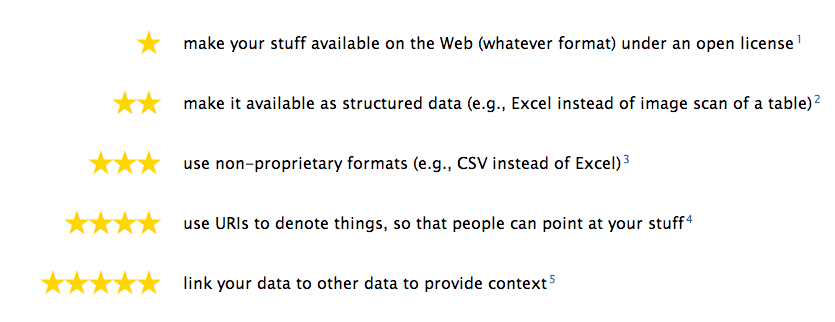

In calling for ‘Raw Data Now’, Tim Berners-Lee set out a progressive model for open data publication in the ‘Five Stars of Linked Data’ (Berners-Lee, 2010). This calls on governments to place data online in any format, to move towards making it machine readable in open formats, and then ultimately to complement these accessible datasets with standardised and linked datasets, supporting citizens, entrepreneurs and government itself to connect up disparate data across the web.

In this model, the perfect should not be the enemy of the good: government should get data online, and then should work to improve it - lowering the technical and legal barriers that might prevent it being re-used - and adding value to it through linked data. In the Open Data Barometer, we used a 10-point checklist to assess the relative openness of 14 different categories of data in each country: addressing not only the availability, format and license of data, but also how easy it was to discover, and whether it was a one-off data dump, or a sustainable on-going stream of high-quality and timely data. In addition to assessing the extent to which governments were publishing open data, we also looked at the wider climate of open data publication in each country with questions on academic, civil society and business publication of open data, although to maintain the focus of the overall ODB rankings on central government OGD actions, these are not included in the overall scoring framework.

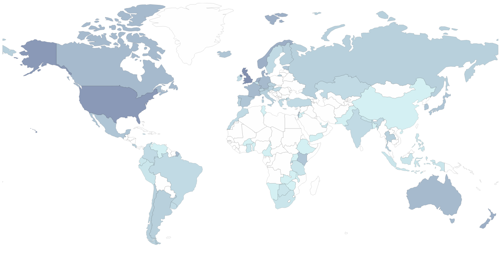

The heat map below contrasts with the previous map of policy diffusion, showing the availability of open data currently lags behind the formation of open data policies in many countries.

Figure 3: Heatmap of ODB Implementation score by country - based on openness of 14 key datasets.

Just 71 of the datasets assessed in the Open Data Barometer study were available as full open data (6.6%), and just 13 (1.2%) were published with clear URIs for key elements in the data in ways that would support linked data publication (for 4- or 5-star Linked Open Data). Even removing the 257 cases in which national governments do not hold the data surveyed (for example, in some countries company registration or cadastral information is only held at a state or local government level), we still find less than 1 in 10 datasets are published as full open data (71 of 821). In particular, many datasets that were otherwise available were published under restrictive licenses, or without clear license terms – and many datasets were not available for bulk download.

The most common file-format for published data was Excel (approximately 280 datasets) with many of these datasets providing only aggregated data. CSV was the second most common format, with over 130 datasets available in this format. Around 80 datasets were available in XML format. Overall these figures suggest that we are still at an early stage of making data available and open online, with the majority of available government data currently meriting only one or two stars on the five-star scale.

Which data is being made available?

It doesn’t just matter that governments are publishing data: it matters what that data is. Whilst countries may boast of the hundreds of datasets they have published online, if these are not the data demanded by citizens, or the kinds of data that can enable transparency, accountability, innovation and greater inclusion, then there may be little potential for an OGD initiative to deliver impact.

In selecting datasets to include in the Open Data Barometer study, we sought to include a breadth of categories that represent both the different functions of government, and the different kinds of data that particular re-users of data may be interested in. We paid close attention to selected datasets that had a high likelihood of being available across diverse countries, and we provided guidance to researchers on a dataset-by-dataset basis to deal with cases where data might be only available at a sub-national level. Table 3 below shows how the datasets included in the Open Data Barometer represent a range of different potential uses of data. Of course, the nature of open data means categories are not mutually exclusive: the same dataset might be useful across social policy, innovation and accountability arenas. Future work is needed to unpack which datasets contribute most to certain kinds of impacts in different contexts, and how the technical features of those datasets affect their use.

| Innovation Cluster | Social Policy Cluster | Accountability Cluster |

|---|---|---|

| Data commonly used in open data applications by entrepreneurs, or with significant value to business. | Data useful in planning, delivering and critiquing social policies & with the potential to support greater inclusion and empowerment. | Data central to holding governments and corporations to account. Based on the ‘Accountability Stack’ proposed by Perrin (2012). |

| Map Data; Public Transport Timetables; Crime Statistics; International Trade Data | Health Sector Performance; Primary or Secondary Education Performance Data; National Environment Statistics; Detailed Census Data; Land Ownership Data; | Legislation; National Election Results; Detailed Government Budget; Detailed Government Spend; Company Register |

Table 3: Dataset clusters used in Open Data Barometer analysis

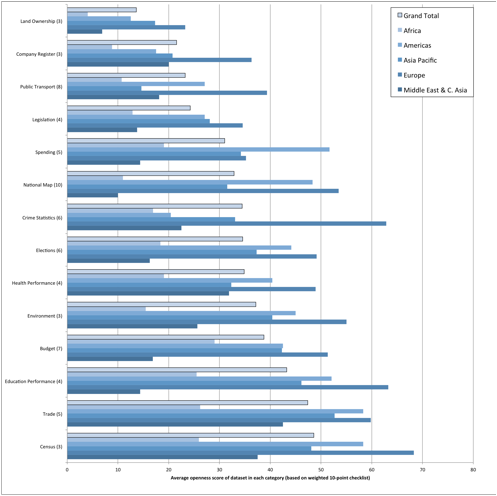

Figure 4 below shows the average score each dataset received in each region, along with the global average. The number in brackets shows the number of datasets in each category that were found to meet the full Open Definition requirements of being machine readable, accessible in bulk, and openly licensed. Through this we can see considerable variation in the kinds of data being made available.

Census and trade data, generally supplied by national statistical agencies score highest on this scale, reflecting the capacity of statistical agencies to provide timely and regularly updated datasets, and the widespread existence of online platforms for accessing machine-readable extracts of statistical agency data. However, many of these datasets fall short of meeting the open definition due to the absence of a clear open license statement, or limitations preventing re-users from accessing bulk extracts of the data – instead leaving governments to play an interpretive role in determining what analysis can be made of statistical data.

After statistical datasets, national budgets are the next highest scoring, almost ten points on average ahead of spending data, which is less likely to be published, and when available is often published in very aggregated forms that do not allow citizens to drill down to track government transactions in detail. Least likely to be openly available are Land and Company Registration data, reflecting both the absence of coherent land and company registry datasets in a number of countries, and a low priority apparently placed by many OGD initiatives on making these datasets available. Given the current political salience of corporate transparency, and the presence of land governance as a high-profile issue on the international agenda, this does raise questions about whether Open Government Data initiatives, as currently constituted, are able to deliver valuable, but potentially contentious datasets, the release of which may threaten entrenched political interests. One of the barriers to the release of these datasets appears to be the established charging regimes, in which agencies are either funded through sales of data, or where historic conventions of charging for access to paper records have been continued as datasets have been digitised.

Figure 4: Average openness scores by dataset category, using weighted dataset checklist survey responses.

Across the datasets available, there was very little evidence of standardisation, with the exception of Public Transport data, where many data publishers were making use of the General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS). Given the potential value in being able to combine statistics, financial information and company information across borders in order to address key social issues, further work on developing inclusive and open standards is likely to be needed in future.

Not all data is created equal: looking inside the dataset

This report is focussed primarily on our quantitative findings. However, our expert survey also pointed to important issues of data quality and trustworthiness. Of the 113 datasets that were available in machine-readable and openly licensed form, researchers found 15 where the sustainability of their publication was questionable, and 20 that were not up-to-date or published in a timely fashion. Entrepreneurs and businesses are much more likely to build upon data when they are assured about its continued availability, and many forms of citizen action rely on having timely access to data. For example, data on crime that is months old, or not published regularly in the same format, is hard to use to scrutinise police performance, or to power innovative applications.

In their qualitative responses, researchers drew attention to the limited scope of many datasets, particularly in developing countries. For example, researchers reported that education statistics were missing for certain regions, or that health statistics were only provided at very aggregate levels. In many countries public transport data is unavailable, either because it is not managed in any structured way (see for example (Raman, 2012)) or because no public transport services exist. The reliability of key datasets in some countries was also raised as a significant issue. For example, in Chile, the 2012 Census data were called into question due to methodological flaws, and the results have now been withdrawn. In viewing the Open Data Barometer results it is important to be aware that not all data is created equal, and a full assessment of the potential of open data in each country needs to look in more depth at the particular histories of each dataset (Gitelman, 2013; Rosenburg, 2013).

One of the reasons that innovators value government data is its reliability, standardisation and comprehensiveness (Lakomaa & Kallberg, 2013). In well-resourced states, few other institutions can provide such consistent data covering the whole country. This makes open data, or Public Sector Information, a valuable input to economic activity. However, where government capacity is limited, the data available might not have these properties. This suggests that alternative approaches to using open data for innovation, and for securing accountability, will need to be explored in many developing countries, and raises questions about how far applications from one context can easily be transferred to another. Securing benefits from open data is likely to require contextually aware capacity building: rather than the implementation of top-down training templates.

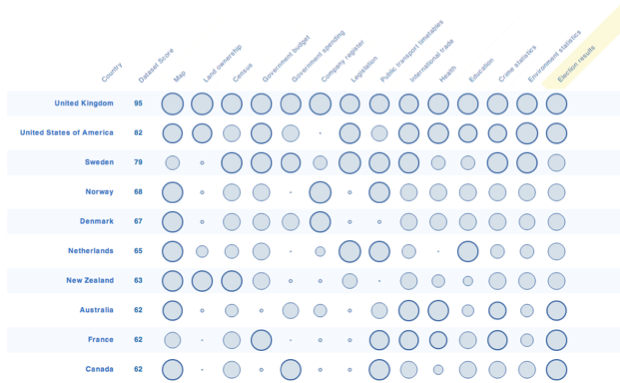

Full data availability listings

In total, the Open Data Barometer has collected information on the availability of 1078 different datasets across 14 categories, looking at a range of aspects of data availability and openness (including online availability, machine-readability, license, sustainability, timeliness of updates and discoverability). The matrix overleaf sets out the scores assigned for each category of data by country, with larger circles representing greater openness, and a thick outline given to each dataset which meets the full open definition.

Key

Circle size represents openness score.

Thick outline represents data a dataset meeting the open definition criteria

The overall dataset score (column 2) is the average of individual dataset scores for a country. Scores are awarded on a 0 – 100 scale, based on a weighted 10-point checklist. For the weights given to each question see Table 6 in the methodology Annexe. 60% of the overall score is made up by the components of the Open Definition (OKF, 2006).

Datasets

Early indications of impact

Few methods exist for assessing the impacts of open data publication. Whilst in a number of countries studies exist that have estimated the economic potential of open data, across our 77-country research we could not locate any comprehensive evaluations that quantify the benefits of open data. This is unsurprising given the very early stage of open data initiatives in most countries, although it does highlight a key challenge for research in the coming years.

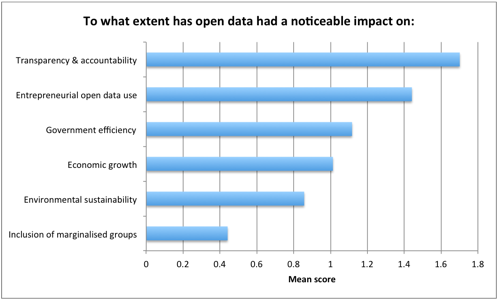

To help inform the development of future impact measurement methods, we asked our expert survey researchers to look for media and academic mentions of where open data had been used, and had been cited as the cause of some substantive change, across a range of different settings, including government transparency, government efficiency, environmental sustainability, social inclusion, economic growth and entrepreneurial activity. The more mentions of impact, and the more substantial the impact mentioned, the higher the score researchers could grant a country on each of these dimensions. Although this does not offer substantive proof of impact, it does allow us to start exploring the relative emphasis on different kinds of open data impacts currently seen in different countries.

Figure 5 shows the non-normalised mean impact score given against these different categories. Researchers could award scores on a 0 – 10 scale. The median score awarded across all six of the impact questions asked was 0, with the exception of accountability, with a median score of 1. Excluding countries with a low score on variables for the presence of OGD initiatives marginally increases the mean, but does not alter the ordering of the categories.

Figure 5: Average across all countries of response to expert survey question of the form 'To what extent has open data had a noticeable impact on...X' (see Annexe for question wording). Non-normalised values to allow comparison between questions.

Stories of open data impact discovered across the ODB survey were most likely to focus on accountability, closely followed by entrepreneurship and the creation of innovative applications or start-ups. Many of these enterprise stories were closely related to app competitions and hack-days, highlighting the importance of activity to stimulate the economic re-use of open data, although researchers noted that few hack day events were rigorously evaluated. Environmental and social inclusion impacts of open data are the least cited, suggesting that there is much more work to be done to explore and stimulate potential uses of open data in these areas. In particular, there may be scope for more sectoral capacity building around open data.

Global snapshot: conclusions

From this global snapshot we can see that whilst OGD policy has spread rapidly, and in a number of regions there are strong government, business and civil society foundations for open data initiatives, we are still a long way from seeing widespread implementation and impacts of those policies, in terms of data published and used, with uses and their consequences evaluated.

In the following section we turn to a comparative country analysis of the Open Data Barometer survey to explore in more depth the kinds of activities that leading countries are undertaking to build their open data programmes, and to identify different patterns of OGD development around the world.